25/10/2022

When cultural heritage becomes cannon fodder

- The war in Ukraine has once again highlighted the non-compliance with common agreements for the protection of cultural heritage and infrastructure.

- The 1954 Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict is the frame of reference in this area, but the challenges are still numerous.

- According to experts, spaces for debate, reflection and public awareness are essential to avoid the destruction of cultural goods in the future.

Whatever the causes, the results of armed conflicts are always the same: they involve atrocious loss of civilian life, massive displacement and violations of international humanitarian law and human rights. One of the expressions of this last consequence is the destruction of cultural heritage, with the will to demoralize, humiliate and often completely eliminate the adversary. The war in Ukraine has once again highlighted the non-compliance with common agreements on cultural heritage and infrastructures, and has brought back to the table the challenges that still need to be met in this regard.

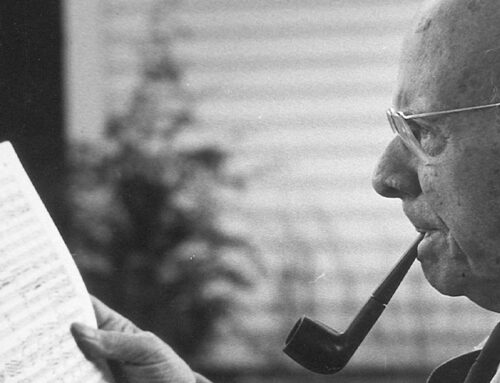

Reflection on this issue will guide, on October 27, the first international conference of the Pau Casals Chair in Music and the Defense of Peace and Human Rights, promoted by the Pau Casals Foundation and the Universitat Oberta de Catalunya (UOC), which promotes research, knowledge, dissemination and contemporary debate on the musical and humanistic dimension of Pau Casals and his legacy, as well as the values he defended throughout his life.

Erasing the footprint of a community

More than 150 cultural sites have been destroyed in Ukraine – partially or completely – as a result of the fighting since the beginning of the Russian offensive against the country. Among them, 70 religious buildings, 30 historical buildings, 18 cultural centers, 15 monuments, 12 museums and 7 libraries have been damaged, according to the latest UNESCO report. It is the umpteenth brutal expression of the concept of total war, with direct consequences on heritage, which humanity has already witnessed on countless previous occasions. Well alive in the collective memory are the examples of the violations in the Balkan conflict (1991), against the Buddhas of Bamiyan (2001), during the Iraq war (2003) or, more recently, in Syria (2011), to mention a few.

“The main objective of cultural cleansing is clearly to destroy the cultural heritage of the adversary or the opposing ‘ethnic group,'” says Jan Hladik, a program specialist at UNESCO. “Moreover, this destruction is often facilitated by geographic proximity and mutual knowledge of sites and cultural heritage, as well as of the adversary’s culture,” he adds. For Alfons Martinell, professor emeritus at the University of Girona (UdG) and honorary co-director of the UNESCO Chair in Cultural Policies and Cooperation at the same university, these types of practices make clear the words of George Steiner and Walter Benjamin that culture is not exempt from barbarism, and want to prevent future generations from being able to recover collective memory. “Memory is a human attitude of wanting to know where we come from and what has happened,” says Martinell, who points out that it is essential “to build our personality and our present and, above all, to build futures.”

Although it has been recurrent throughout history, the destruction of cultural heritage has been even more devastating since the introduction of aerial bombing and long-range weapons. World War I resulted in the destruction of a great deal of cultural heritage in Reims, Louvain and Arras, among others, but World War II was even more traumatic, due to the regular nature of the bombings, the export of cultural property from occupied territories and, of course, the geographic scope and duration of the conflict.

Many important lessons have been learned since World War II, such as “the need for peacetime preparatory measures to protect cultural heritage – such as the establishment and regular updating of inventories of movable and immovable cultural heritage, the training of the military to respect cultural heritage, the introduction into criminal codes of penalties for crimes against cultural heritage, and the prosecution of individuals who have committed or ordered crimes against cultural heritage,” Hladik summarizes.

The culmination of these considerations was the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, which came to consider cultural heritage as an asset of humanity and is today the reference framework in this area. “It is essential to protect cultural property because it is not only the heritage of a specific group or nation – even if they often want to identify with them and even if their destruction is an instrument to hurt the enemy – but of all humanity. If they were only particular assets of each culture, they would also have to be preserved out of a principle of respect and tolerance; but they are much more: they are a permanent legacy of the experience of the whole world,” notes historian Joan Fuster-Sobrepere, director of the UOC’s Faculty of Arts and Humanities and co-director of the Pau Casals Chair in Music and the Defense of Peace and Human Rights, by way of summarizing the fundamental concept guiding the text. “Each culture and each testimony of the past are unique and cannot be sacrificed by one generation in their quarrels,” he adds.

Debts and challenges in the area of heritage protection

In this context, how can international solidarity be fostered and the collective response improved to ensure heritage protection? According to Hladik, most of the work involves raising public awareness.

Fuster-Sobrepere expresses himself along the same lines. “It is important to revalue the 1954 declaration, to make it known. The population must be made aware of the values of respect and tolerance, as well as promoting the culture of peace and the cultural rights of people. Firm opposition to supremacist ideas is necessary, and we must prevent them from growing within our societies,” the expert believes. “One cannot be too optimistic about the possibility that certain rules and limits will be respected in a war, but ultimately it is necessary for public opinion to be aware of these rules of respect and to mobilize to enforce them,” he adds.

“Beyond conventions, agreements and international law, there is the sensitivity of the entire population for which this must be preserved and protected,” says Martinell in the same vein. “We believe that from the Pau Casals Chair of Music and Defense of Peace and Human Rights we can offer this space for reflection and these proposals for the future,” he concludes.

Conference: Culture and Heritage at War

- October 27, from 10 a.m. to 5.30 p.m.

- In the Pati Manning of the Center for Cultural Studies and Resources (CERC) (c/ Montalegre, 7, Barcelona)

- Program

- Registration

The conference will be inaugurated by the director of the Pau Casals Foundation, Jordi Pardo; the vice-president of the Pau Casals Foundation, Narcís Serra, and the director of the UOC’s Faculty of Arts and Humanities and co-director of the Pau Casals Chair in Music and the Defense of Peace and Human Rights, Joan Fuster-Sobrepere.

Some of the international expert voices that will make this analysis possible are the former secretary of the 1954 convention, Jan Hladik; the Syrian archaeologist and president of Heritage for Peace, Isber Sabrine, and one of the most renowned specialists in Cultural Law, inspirer of the Ibero-American Cultural Charter and professor emeritus of the UNED, Jesús Prieto de Pedro.